Global average surface temperature data clearly indicate that we are now living in a fundamentally different world from that of our grandparents’ generation. Records from 2024 show that the world has crossed a critical “threshold,” with global average temperatures rising by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius. While this increase may appear modest, even small differences can have profound impacts on the climate system—intensifying disasters and making them more frequent than in the past.

Thailand has recently witnessed tragic scenes and severe damage in its southern region, particularly in Hat Yai, where hundreds of thousands of residents were forced to evacuate their homes. Flooding far more severe than anticipated caused massive economic losses and resulted in hundreds of officially recorded fatalities.

However, this catastrophe was not confined to Thailand alone. Around the same period, several countries across Asia also faced extreme disasters. In Sri Lanka, for example, flooding from Cyclone Ditwah was initially expected to reach around half a meter, but water levels surged to nearly four meters. Meanwhile, Cyclone Senyar, which struck Thailand, continued on to affect Sumatra in Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula. Altogether, more than 1,750 people across the region lost their lives as a result of this series of disasters.

This catastrophe was not confined to Thailand alone. Around the same period, several countries across Asia also faced extreme disasters. Altogether, more than 1,750 people across the region lost their lives as a result of this series of disasters.

Scientists agree that these extreme weather events are “not normal,” with climate change driven by carbon dioxide emissions from human activities identified as a key cause.

Undoubtedly, we must urgently reduce greenhouse gas emissions to prevent the climate crisis from worsening beyond its current state. At the same time, governments must adapt to this “new world” of rising temperatures—particularly by strengthening their capacity to respond to disasters that are likely to become more frequent and more severe.

Traditionally, governments have relied on reactive (ex-post) financial mechanisms to cope with unexpected disasters. These include drawing on contingency budgets, reallocating public spending, issuing emergency borrowing decrees, or seeking international assistance. In this article, however, I would like to introduce a proactive (ex-ante) financial instrument for disaster risk management: catastrophe bonds, which enable the transfer of disaster risk to investors when unforeseen events occur.

Governments have relied on reactive financial mechanisms to cope with unexpected disasters. In this article, Rapeepat would like to introduce a proactive financial instrument for disaster risk management: catastrophe bonds.

What is Catastrophe Bonds?

In general, fixed income securities are fundraising instruments in which the issuer is the borrower and investors act as creditors. Issuers are required to pay interest at a predetermined rate on a regular basis and to repay the principal in full at maturity. Familiar examples of government debt instruments include treasury bills, with maturities of a few months, and government bonds, which can extend up to 30 years. These instruments essentially represent the government borrowing from investors to finance public policies, compensating them through interest payments and returning the principal upon maturity.

Catastrophe bonds, however, despite being labeled as “bonds,” function more like insurance products in practice. The funds raised through catastrophe bonds are not spent immediately. Instead, the issuer can only access the funds if a disaster event—defined by pre-agreed conditions—occurs. During the bond’s lifetime, the issuer pays investors relatively high interest rates, typically around 8–10 percent. If the bond reaches maturity without any qualifying disaster occurring, the issuer must repay the full principal to investors.

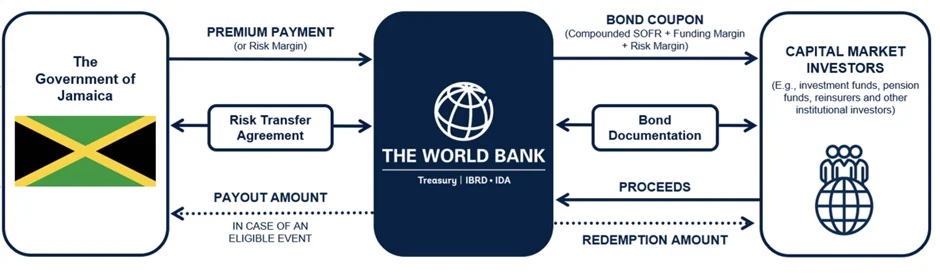

Because of this unique structure, catastrophe bonds require an intermediary. When issued by the private sector, a special purpose vehicle (SPV) is typically established to manage the pooled funds. In the case of developing-country governments, highly credible international institutions—most notably the World Bank—currently play this intermediary role. The World Bank enters into a risk transfer agreement with the issuing country while simultaneously offering catastrophe bonds to investors.

This mechanism not only reassures investors but also ensures that the associated liabilities do not appear on the government’s balance sheet. As a result, catastrophe bonds do not affect the public debt-to-GDP ratio and provide governments with greater fiscal flexibility.

At the heart of catastrophe bonds lies the definition of a “trigger”, which determines whether principal payments from the bond will be released to compensate for disaster-related losses. In general, trigger mechanisms fall into two main categories: indemnity triggers and parametric triggers.

Indemnity-based triggers operate in a manner similar to traditional insurance payouts, a system familiar to many. After a disaster occurs, the issuing government assesses the actual losses incurred and then claims compensation from the funds raised from catastrophe bond investors. While this approach ensures that payouts closely reflect real damages, the loss assessment process is often time-consuming and carries the risk of inflated or disputed claims.

Parametric triggers, by contrast, are based on the physical characteristics of a disaster, such as wind speed in a storm, earthquake magnitude, or cumulative rainfall over a specified period. This approach is transparent and verifiable, as it relies on scientific data, and allows for rapid disbursement of funds to support recovery efforts. However, its key drawback is basis risk—the possibility that a country may suffer significant damage from a disaster but receive no payout because the event fails to meet the predefined trigger conditions. For example, if a trigger is set for earthquakes of magnitude 7.0 or higher, an earthquake of magnitude 6.9 could still cause severe damage, yet no compensation would be paid because the threshold was not met.

Beyond these two primary trigger types, financial practitioners have developed hybrid approaches to mitigate their respective weaknesses. One such option is the modeled loss trigger, which estimates damages using predefined models rather than waiting for ex-post damage assessments, thereby improving transparency and reducing the time required to determine payouts.

Today, the catastrophe bond market has evolved from a niche instrument used primarily by insurance companies into a large-scale market in which governments actively raise capital to hedge disaster risks. The market is currently valued at over USD 50 billion, covering risk transfers related to named storms, earthquakes, wildfires, and even cyber threats. Notable sovereign issuers include the governments of Jamaica, the Philippines, and Mexico.

Case Study: Jamaica’s Tropical Cyclone Catastrophe Bond

Parametric triggers remain the preferred option for sovereign catastrophe bond issuers, as governments require rapid access to funds to support relief and recovery for affected populations. A clear example of successful implementation is Jamaica’s tropical cyclone catastrophe bond, first issued in 2021 and reissued in 2024 upon the maturity of the initial bond.

Jamaica is an island nation in the Caribbean located within the Atlantic hurricane belt. Historically, it has ranked as the third most disaster-prone country in the world, with more than 80 percent of residential properties exposed to hurricane risk. The tropical cyclone bond, intermediated by the World Bank, therefore serves as a crucial mechanism for risk management and for enhancing fiscal stability.

The bond is structured around a sophisticated parametric trigger system, dividing Jamaica and the surrounding ocean into a grid of square “cells.” Payouts are triggered when a tropical cyclone passes through a given cell and meets specified central pressure thresholds—a key indicator of storm intensity, with lower pressure corresponding to greater severity—as illustrated in the example below.

In October of this year, Jamaica was struck by Hurricane Melissa, the most severe storm the country had experienced in decades. Approximately one month after the disaster, the World Bank announced a 100 percent payout of the bond’s principal, amounting to roughly USD 150 million. While this sum represents only a fraction of the several billion dollars required for full reconstruction, it constituted a pre-arranged pool of funding that was immediately available—without the need for additional borrowing or protracted negotiations.

In the case of Thailand, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Panit Watanakul and Asst. Prof. Dr. Wanissa Sueanil from the Faculty of Economics at Thammasat University have published research indicating that parametric catastrophe bonds focused on extreme climate-related disasters would be the most suitable instrument for the Thai context. Such instruments could help reduce the public debt-to-GDP ratio while enhancing fiscal flexibility in responding to flood risks.

As the risks posed by climate change increasingly materialize into real-world disasters, governments worldwide must adapt to this new reality by adopting proactive disaster risk management mechanisms, rather than relying solely on reactive responses and post-crisis financing.