I felt a deep pang of sorrow when I saw the news photos of the floods in Hat Yai—more devastating than any I’ve seen before. Childhood memories of toy shops, candy markets, chicken-rice stalls, and relatives’ homes I once stayed in now lie buried beneath thick brown mud. Though the water has receded, what remains is a chorus of public outrage over the government’s failure to respond to the crisis. The real test begins now: authorities are moving ahead with compensation plans, paired with a much larger question—how do we prevent devastation of this scale from happening again?

Earlier this year, I wrote about the importance of early warning systems and I stand by that argument. Such systems represent one of the most cost-effective investments we can make: they require relatively little capital yet significantly reduce losses. In this piece, however, I turn to a new question—water management. Many countries have already moved beyond heavy “hard-infrastructure” solutions toward nature-based water management systems, with the Netherlands’ renowned ‘Room for the River‘ program as a prime example.

For centuries, the Netherlands has been known globally as a nation in constant negotiation with water. Roughly one-fourth of its land sits below sea level and more than half of it is at risk of flooding. Historically, the Dutch relied primarily on hard infrastructure: dikes, seawalls, flood barriers—structures built with an engineering mindset aimed at defeating nature by separating farmland, residential land, and river space into rigid boundaries.

Yet, as dikes grew ever higher, so too did the risks. Fast, contained water flows meant that if infrastructure failed, the resulting impact would be catastrophic. That fear materialized in 1993 and again in 1995, when the Rhine and Meuse rivers swelled to near-disaster levels. The government ordered the evacuation of 250,000 residents and nearly one million livestock from vulnerable areas.

Although the worst-case scenario did not unfold, these events forced the country to fundamentally rethink its vertical approach to flood control. As climate models indicated that river volumes could exceed historical patterns, the Netherlands faced a critical decision: continue raising dikes—or find a solution that would protect the country without destroying landscapes and ecological functions.

They chose the latter. And that decision marked the beginning of Room for the River.

Reclaiming Space, Reviving the River

The Room for the River programme marks a departure from the Netherlands’ traditional flood-control solutions. Unlike past infrastructure-centric responses, this initiative is designed with two parallel objectives: the long-standing priority of flood safety, and a newly elevated goal—spatial quality. This means infrastructure is no longer conceived solely by civil and environmental engineers, but through collaboration with landscape architects, urban designers, and ecologists, ensuring that these spaces serve multiple purposes rather than merely holding back water.

Launched in 2006, the policy set a ten-year completion timeline, supported by a budget of €2.3 billion (approximately 80 billion baht). More than 30 project sites along the river system were selected, each tailored to its specific context, investment value, and its dual mandate: defence against flooding and enhancement of spatial quality.

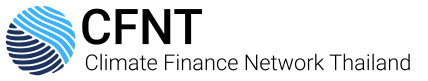

The premise was straightforward. Within ten years, the river management system must be capable of handling water discharge from the Rhine at 16,000 cubic metres per second. The government laid out a set of possible interventions—not as fixed formulas but as options for local authorities to discuss with their communities and select what best fit their landscape. Examples include:

- Deepening floodplains for areas where accumulated sediments obstruct river flow

- Removing barriers to flow wherever feasible

- Relocating dikes further from the river to return more space to the water—suitable for rural regions with available land

- Creating temporary water retention zones for emergency overflow

- Constructing bypass channels where the river narrows, accelerating discharge during peak flow

- Lowering groynes that once protected riverbanks but now hinder water movement

- Dredging the main river channel to increase depth

- Raising embankments

- Reinforcing existing dikes so they stand stronger and higher

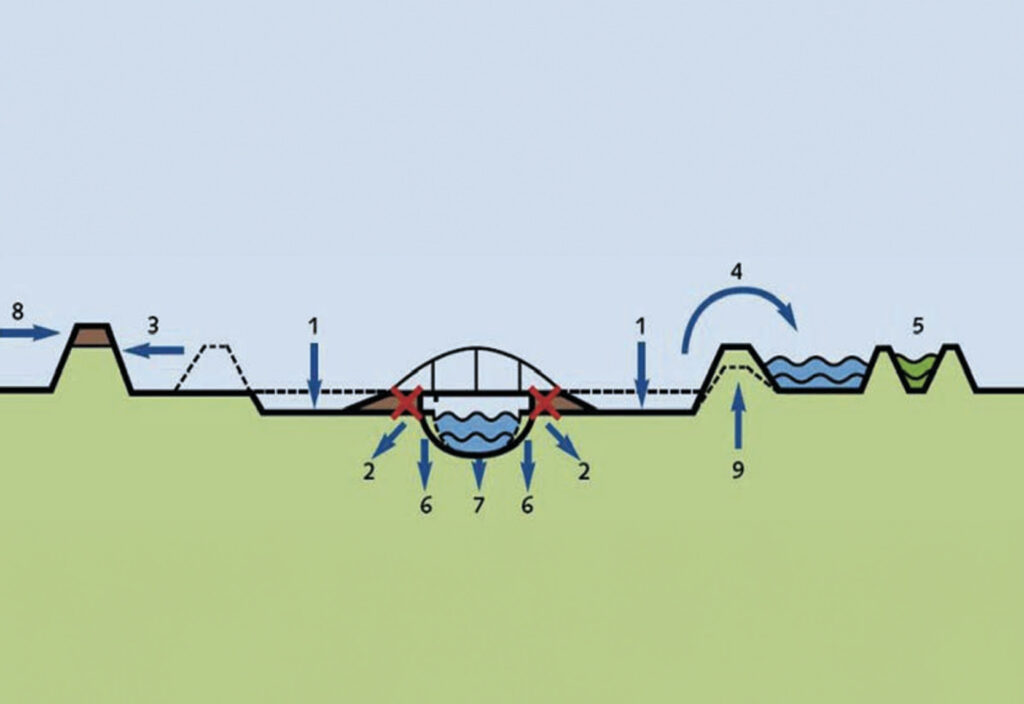

One of the most compelling cases is the restoration of floodplain space along the Vaal River near the city of Nijmegen, carried out between 2012 and 2016. The Vaal is the largest river in the Netherlands, and its sharp bend and constricted channel near Nijmegen had long put the city and its neighbouring settlements at acute risk of flooding.

The project required a profound transformation of both engineering systems and landscape form. The existing dike was moved inland by approximately 350 metres; a new three-kilometre-long, 200-metre-wide channel was excavated parallel to the original river course; and the small island situated between the old and new channels was redesigned as an urban-adjacent public park for recreation and ecological activities. The intervention ultimately lowered peak water levels by 35 centimetres—eight centimetres more than initially predicted.

Naturally, an undertaking of such scale came with significant impacts on those living closest to the river. This is precisely why strong governance, transparent planning, and fair compensation became essential pillars of the Dutch model. And it is here that the Room for the River programme stands out most clearly.

(Down) The implementation plan for the Room for the River Waal project, which includes relocating the dike and excavating a new river channel / Photo from Room for the River Waal – protecting the city of Nijmegen

Participation at the Core

At the heart of the policy lies a deceptively simple principle: the community must participate before construction begins. Central government provides funding and targets, but the design and implementation rest with local authorities. Local governments must open the floor for proposals that address future flood risks while reflecting the needs and identities of the people who live along the water. Should local residents disagree with an option, they are encouraged to propose alternatives that meet the same objectives.

At the heart of the policy lies a deceptively simple principle: the community must participate before construction begins. Central government provides funding and targets, but the design and implementation rest with local authorities.

Yet local governments were not left to navigate this alone. The national government appointed an independent Quality Team—a group of experts in landscape architecture, engineering, ecology, and spatial planning. While they had no formal decision-making power, they acted as advisors, critics, and design mentors, reporting directly to the minister responsible for the programme.

Their evaluation focused on three major criteria:

- Riverside usability – Projects that reduce flood levels but destroy agricultural use, river access, or recreation spaces would fare poorly.

- Aesthetic coherence – New water channels must resemble the language of a natural river, not an engineered drainage line.

- Long-term resilience – Can the project withstand future climate uncertainty and continue functioning beyond a century?

At first glance, such emphasis on spatial quality and participatory process may seem like unnecessary expense. In reality, it is the mechanism that reduces public resistance. The flip side of returning land to the river is that some residents must surrender their homes and fields for the sake of water storage, while the beneficiaries are often those living downstream. Fair compensation and equitable access to redesigned public spaces—riverbanks, parks, ecological corridors—become not merely kind gestures, but moral must-haves.

The programme is widely recognised as a major success and is now being adapted elsewhere in the European Union. It represents a paradigm shift in water management: from dominating the river with concrete to making room for it through coexistence. The Netherlands is currently preparing Room for the River 2.0, expanding its agenda to include freshwater security, drinking water supply, and water quality.

Thailand has spent hundreds of billions of baht on water management, yet some communities remain chronically flooded while others face catastrophic inundation without warning amid confused official communication. This is evidence not of insufficient construction—but of insufficient anticipation. We continue to rely on monolithic, centralised, hard-infrastructure solutions that ignore riverbank users, cultural landscapes, and local ecological systems. The outcome is predictable: sterile floodwalls, blocked vistas, cut-off neighbourhoods, and systems that do not truly manage water.

It is time for Thailand to rethink its approach—to embrace nature-based solutions, community-centred planning, and designs that can cope not only with next year’s rainy season, but with the unprecedented floods that may arrive over the next century. In an era of accelerating climate volatility, we cannot plan solely on the basis of past hydrological records. The river is changing, and so must we.