Every energy planner must balance the “trilemma” of security, equity, and environmental sustainability.

As Southeast Asia becomes the world’s second-fastest-growing electricity market, the region faces two main paths.

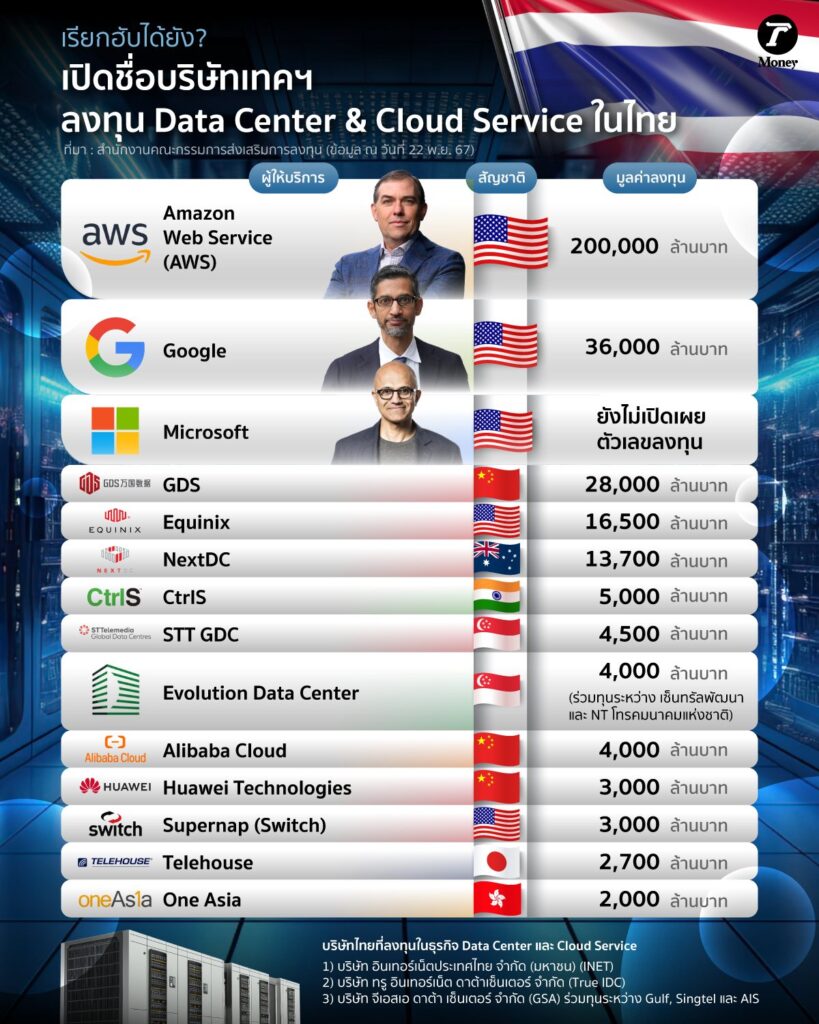

- One is to commit to massive infrastructure to import Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), framing it as a “transition fuel”. This is a move that risks locking our economies into decades of global price volatility, potential cross-border carbon taxes, and billions in stranded assets

- The other path is accelerating renewable energy adoption, which requires a major update of the regional grid.

The Asean Power Grid (APG) is the key physical infrastructure for this energy transition. It is the ultimate solution to this energy trilemma. An efficient grid would enable the region to harness its vast but geographically dispersed renewable energy resources. A fully integrated grid lets this clean power be shared efficiently and in an optimal way.

For example, when solar generation is high in one area, the surplus can be exported to areas where demand is peaking.

The APG enhances regional energy security. A larger, more flexible grid system reduces the region’s dependence on lopsided imports of fossil fuels, and that will make the energy market in the region more resilient. Imagine when countries can share power with their neighbour during a technical failure or an extreme weather event.

$3tn economic prize

A study by the Economic Research Institute for Asean and East Asia (ERIA) estimates that the APG energy trade and supply could lower electricity costs for consumers in the region by as much as 3.9%. At the same time, the whole APG project could add up to US$3 trillion (97.5 trillion baht) in GDP value by 2050 and create 1.45 million jobs regionally.

The APG has been a strategic Asean goal since the 1990s, with an audacious aim of connecting the region’s networks by 2045. Progress has been steady. As of late 2024, nine of 18 priority projects are operational, translating to 7.7 gigawatts (GW) in capacity.

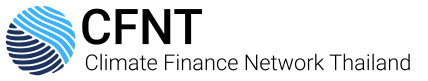

However, this is only a fraction of what is required. This capacity must be more than doubled by 2040 to support regional growth, according to the Asean Centre for Energy (ACE). This need is even more urgent as Southeast Asia becomes a global hotspot for data centres, which require vast amounts of stable, clean electricity.

This is not only a regional problem but also presents an acute challenge for Thailand. While the data centre investment is welcome, news reports have highlighted growing concerns about grid strain and the potential for power instability.

Thailand’s current role in the APG is as the region’s central “interconnector”, for example, through the Laos-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore Power Integration Project (LTMS-PIP). However, the APG is no longer just a source of transit fees.

If Thailand is to achieve its 2050 net-zero target, per its recently published NDC 3.0, a high level of renewable generation is a must. Supporting this national target while simultaneously meeting the high electricity demand from new data centres will depend heavily on a fully functional and expanded APG.

The primary obstacle is not vision, but finance. The Asean Interconnection Masterplan Study (AIMS) estimates that $800 billion (26 trillion baht) is required for the necessary transmission and power generation with high levels of variable renewable energy adoption.

Recognising this gap, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank Group, in partnership with the Asean Secretariat and ACE, launched the Asean Power Grid Financing Initiative (APGF) in October. This platform aims to mobilise large-scale capital by offering technical assistance to prepare bankable projects.

The Bankability Problem

The new APGF is a crucial starting point, but it is not a complete solution for an $800 billion challenge. As the International Energy Agency highlights, the cost of capital in Asean remains significantly higher. Public finance alone is insufficient.

The core task is “crowding in” private capital, which is difficult because these projects are inherently risky: they have massive upfront costs, long payback periods, and are highly illiquid.

Therefore, Asean must leverage this new platform to deploy a proven toolbox of innovative financing instruments, drawing lessons from global successes.

First, we need an innovative framework that protects both private investors and consumers. Under this model, regulators set a revenue floor, guaranteeing the project a minimum income to make it bankable. They also set a cap, which returns excessive profits to consumers.

This model, used to finance the €1.6 billion (60 billion baht) North Sea Link interconnector between the UK and Norway, balances risk and has successfully unlocked billions in private capital by giving lenders the revenue predictability they need.

Second, Asean must implement blended finance to bridge the remaining risk gap. For instance, Partial Risk Guarantees (PRGs) are the ideal tool to solve the problem of creditworthiness for some state-owned utilities.

Another key tool is First-Loss Capital, where public funds take a first-loss position, absorbing initial losses before private lenders are affected. Such an approach can make the investment less risky for investors, thus attracting much-needed private investment.

Asean can also expand its sustainable bond market. In 2024, this market grew by double digits. Under this, Asean+3 stands as the second-largest sustainable bond market globally, following the European Union.

The latest version of the Asean Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance considers grid infrastructure — including transmission and distribution — as “green” provided it enables the integration of renewable power. This gives us a direct, certified tool to attract a new class of global ESG investors to fund APG projects and may mitigate the high capital cost issues.

Third, Asean should consider creating a dedicated regional fund, modelled on Europe’s Connecting Europe Facility (CEF). The CEF provides direct grants for projects with high societal benefits but low commercial returns. For example, the €1.6 billion Celtic Interconnector between Ireland and France received a €530 million CEF grant. This public co-investment covered one-third of the cost, making it bankable for a syndicate of private lenders that included Danske Bank, Barclays, and BNP Paribas. An Asean-led fund could serve the same catalytic role for our most strategic interconnectors.

The Political Inertia Challenge

However, beneath the financial challenge lies a deeper hurdle: political inertia. As South America’s experience shows, the primary barriers can be political fragmentation and regulatory disharmony.

Their solution was to use funding for the soft infrastructure first — the technical studies and negotiations to harmonise rules and agree on fair cost-benefit allocations. This political and regulatory groundwork is the essential prerequisite for any financing.

We must now wield these tools with urgency. Financing the APG is not just an infrastructure project; it is the most critical economic decision we can make to accelerate the renewable energy adoption, resolve our energy trilemma and secure a truly sustainable and independent energy future for the region.

First Published on Bangkok Post