In the global discourse surrounding greenhouse gases (GHGs), carbon dioxide has traditionally been the focal point. However, it’s the less-discussed methane that presents an insidious challenge. Methane, comprising over 70% of natural gas, is accountable for nearly half of the current rise in global average surface temperature. In the past two-decade, methane has proven to be 80 times more potent as a GHG than carbon dioxide.

The perils of methane have come into sharper focus following COP26 in Glasgow. The conference underscored methane’s efficient heat-trapping capacity and its shorter atmospheric lifespan. Consequently, nations pledged under the Global Methane Pledge to cut emissions by 30% in a decade. The subsequent COP28 was shrouded in controversy and skepticism, particularly given the host’s status as a significant oil exporter, potentially at odds with the fossil fuel reduction narrative. Nevertheless, there is a glimmer of hope that these discussions might compel fossil fuel giants to engage in stronger climate action.

After arduous discussions, a small milestone stone was achieved when 50 oil industry leaders signed the Oil & Gas Methane Partnership 2.0 (OGMP 2.0) to eliminate methane emissions. However, this initiative is not immune to criticism, with detractors labeling it as mere ‘greenwashing’ for its lack of commitment to curtail fossil fuel consumption.

Nonetheless, this development, though not revolutionary, signals a pivotal shift. Historically, the fossil fuel sector is known for its climate skeptic stance and has posed legislative roadblocks. However, it is now inching towards acknowledging its complicity and role in the environmental crisis. This pivot, commencing with addressing the pressing issue of methane, might not be the ultimate solution, but it’s a small steppingstone into the right direction.

Where does Methan come from?

Methane, a significant climate change accelerant, originates from three key human-related sectors. Firstly, the energy-industry activities, involving exploration, production, and transport, serve as a primary source. Agricultural sector comes second, particularly livestock rearing and rice cultivation, which play a significant role. Thirdly, methane emissions come from landfills although natural sources, especially wetlands, account for around 30% of methane emissions.

COP28 turned its spotlight on the oil and natural gas sector, driven by advancements in leak detection and prevention technologies and a growing legislative focus on methane. A case in point is Stavanger, Norway’s oil and gas hub. Since 1971, Norway has banned flaring at its North Sea gas platforms to prevent methane leaks, making its oil and gas industry one of the least greenhouse gas-intensive, especially compared to Britain.

Without resorting to flaring for electricity on these platforms, oil firms have to invest in alternative solutions such as mainland electric connections and offshore wind projects. If global oil and gas drilling were to match Norway’s emission intensity, methane emissions could drop by 90% according to The International Energy Agency.

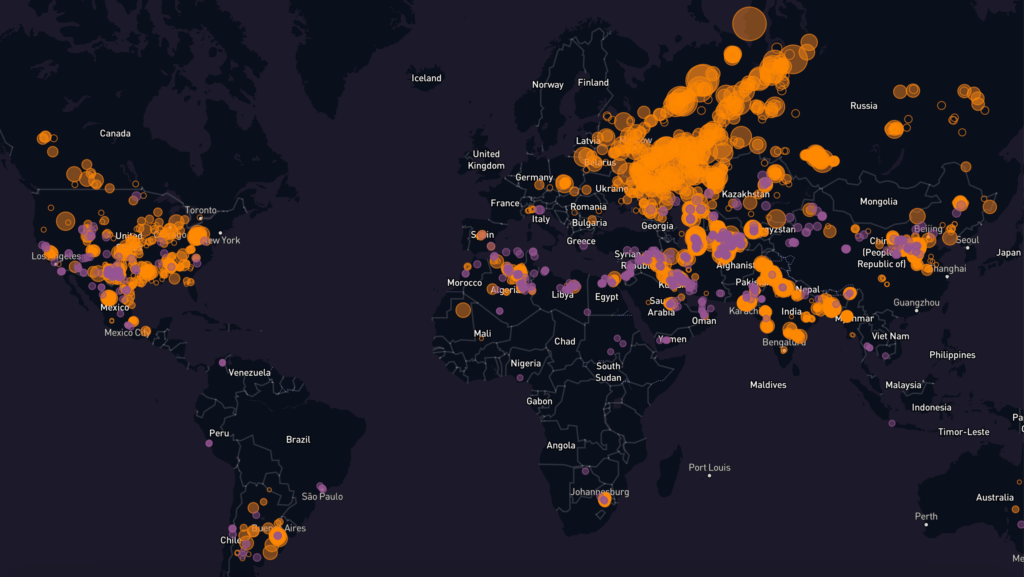

Innovations in methane detection are also noteworthy. Satellites, aircraft, and ground sensors, coupled with artificial intelligence, could now be used to map global methane emissions, pinpointing leak hotspots. Using these technologies, key areas of concern including Algeria, the United States, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan have been identified as regions with significant methane emissions leakages.

In the political sphere, there’s a growing awareness of methane’s role in climate change. China, as the world’s largest methane emitter, has announced plans to target methane in its national climate strategy. The United States is also setting new standards for its oil and gas industry to adopt advanced technology for methane reduction. The European Union has also followed by implementing stringent standards to limit methane emissions in both domestic and imported energy sectors.

This advanced technology for detection and mitigation in combination with rigorous regulations, points towards a promising trajectory for achieving methane reduction targets. It signifies a significant milestone in the collaborative endeavor to combat climate change.

Thailand’s Methane Emission Landscape

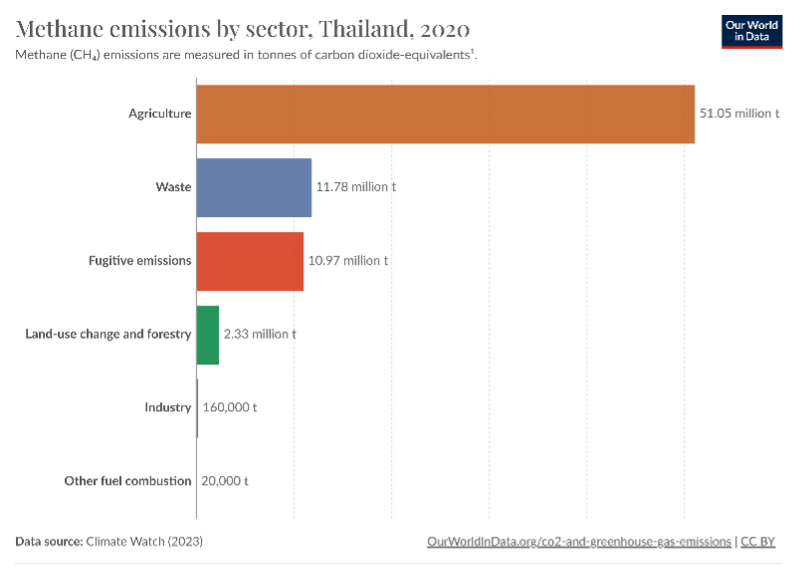

Thailand is positioned as a moderate methane emitter, with its primary methane emissions stemming from agricultural activities, notably rice paddies, which are prevalent throughout Southeast Asia..This pattern is similar throughout the Southeast Asia where the cultivation of wet rice is universally practiced and deeply ingrained in regional culture. Additionally, significant methane contributions come from landfills and the oil and gas industry, known for their release of ‘fugitive emissions’ during drilling and transportation processes.

PTT Exploration and Production Public Company Limited (PTTEP), a state-owned Thai entity, has joined The Oil & Gas Methane Partnership 2.0. The company began tackling methane emissions in 2016. However, Thailand’s limited natural gas reserves and increasing reliance on imports mean this commitment may have a limited impact on the country’s overall emissions.

In addition, Thailand’s absence from the Global Methane Pledge at COP27 is disappointing. Former Minister of Natural Resources and Environment, Varawut Silpa-archa, attributed this decision to the predominantly agricultural source of the country’s methane emissions, over which he claimed limited authority to enact unilateral decisions.. Consequently, Thailand’s stance aligns it with Laos and Myanmar, marking a divergence from several of its ASEAN counterparts such as Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia, all of which have committed to the pledge.

Thailand’s reluctance to commit, despite its relatively high middle-income status, poses a significant transition risk. With the increasing momentum of global efforts to reduce GHG emissions, nations are taking proactive measures. Delayed actions could lead to sudden, enforced changes, as exemplified by initiatives like the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which could impose additional costs on imports with high carbon footprints.

The looming threat of a ‘methane tax’ on key exports of Thailand such as rice could pose significant disadvantage to the country, especially as competitors are shifting towards low-methane agricultural techniques. Thailand’s agricultural sector remains in the vicious cycle of subsidy and relief, reflecting a government hesitant to initiate transformative changes.

*Originally published on The Momentum.